Opening Shutters, Opening Minds

With my gardening efforts once again curtailed by the weather on Sunday, I shut myself away in the sanctuary of my greenhouse and, as the rain battered against the roof, sat down to read ‘Loud and Clear’.

Link: lifechangestrust.org.uk/…/news-20-years-activism-people-dem…

Published by the Life Changes Trust, ‘Loud and Clear’ offers a historical account of how people living with dementia in Scotland have become activists and influencers in their own right over the last 20 years. It’s a delight. I got so caught up in the story of their successes and their struggles that I didn’t even notice when the rain stopped.

A few key figures feature strongly in the book and the author, Philly Hare, rightly makes no apology for this – it is simply an honest reflection of the enormity of their contributions both to the dementia movement and to the book itself. From a project perspective, it was lovely to learn more about the back story of Nancy McAdam, who has kept the bold Highland group firmly grounded. Nancy’s antics with fellow dementia activist Agnes Houston were mostly familiar to me, but I knew nothing of her history of community activism, such as protesting about GM crops and even spending a night in the cells. This brought a huge smile to my face – Nancy has lost none of her feistiness.

In introducing the book, the Trust’s Arlene Crockett observes that the courage and energy of the activists has inspired many individuals and in some cases has influenced their working practices and life courses. I am just one of those many individuals. The story of the ‘founding father’ of the Scottish movement, James McKillop, took me on a trip down memory lane. I met James only a handful of times and yet his influence on my work was profound.

James was diagnosed with multi-infarct dementia in 1999 at the age of 59. He had already been campaigning for several years when I met him and his wife Maureen in 2007. At that time I was the digital storytelling lead for the former Joint Improvement Team and working closely with Emma Miller to support a shift in care and support planning approaches. This required moving away from a tick-box approach to assessment that identified people’s deficits and needs and matched them against a menu of one-size-fits-all services. The alternative focus on ‘personal outcomes’ was based on having a conversation to understand what matters most to a person in a whole life context and the contributions he or she could make, with the right support, to achieving this. The McKillops demonstrated extraordinary generosity, inviting Emma and me into their home on several occasions and giving up a lot of their time to share their triumphs, challenges and insights with us. Their digital stories illustrated perfectly the impact of the two very different assessment approaches on each of them and on their life together. They were shown at various national conferences and featured on a DVD which was used extensively as a training resource for many years.

One of the stories that James told called ‘Finding the Right Words’ proved to be a particularly valuable communication aid. He highlighted the importance of finding the right words when diagnosing dementia, communicating with someone with dementia as a care professional and as friend and crucially, when talking about someone with dementia. He did so in such a compelling way that he greatly increased my understanding of the importance of language and the need to pay attention to it. Although James spoke about the difficulties he sometimes experienced himself in finding the right words on account of his condition, in the digital stories he demonstrated am uncanny knack of finding just the right words. These words kept the message simple and at the same time smashed the old cognitive impairment: wisdom binary to pieces. For instance, he advised that if the dementia activists were really going to make a difference, there was little point ‘preaching to the converted’. Instead they needed to speak to people who had ‘different ideas about what someone with dementia could do’ and to do that effectively, you had to ‘know your audience’. That meant listening. Indirectly, James’ eloquence also caused me to think about people who might struggle to find the right words, or perhaps were unable to find words at all. This prompted me to use more creative methods in my story work and to explore and put the spotlight on alternative forms of expression in my ‘personal outcomes’ work.

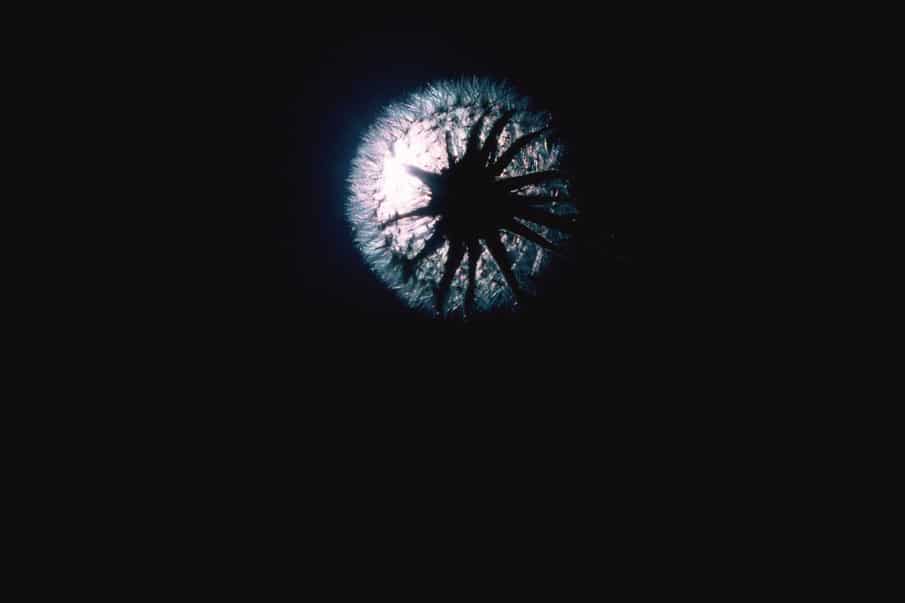

James’ generosity didn’t stop with the giving of his time and words of wisdom. Digital stories combine words and images and he gave me permission to use a truly stunning collection of photographs that he had taken. Twelve of these photos had featured in a calendar that he’d produced with his Alzheimer Scotland support worker, Brenda. James once again succeeded in finding the right words by giving the calendar the provocative title ‘Opening Shutters, Opening Minds’. It certainly opened my mind. Not only were the photographs remarkable, but James informed me that he had recently been ‘retaught’ how to use a sophisticated camera by Brenda. Retaught? At the time I had assumed that this wasn’t possible for someone with dementia. The camera itself held huge symbolic significance – it too had ‘Opened Shutters’ – in the form of conference doors. I learned that Brenda had slung the camera round his neck to enable him to gain entry to a dementia conference in the guise of a photographer because he had previously been refused entry on account of having dementia! This refusal had taken place as recently as 2000. I was staggered.

James caused me to think long and hard about the retained capabilities, potential and many different types of contributions that people with dementia continue to make to their own lives and the lives of others, often unseen. He also made me think about other perhaps less obvious instances of discrimination, exclusion and denial of opportunity for participation experienced by someone with dementia in ordinary, everyday life situations. When I later developed a series of digital stories to explore this I called it ‘Challenging Assumptions’ to acknowledge my conversations with James. I also used the attached photograph from his Opening Shutters collection on the front cover. This photograph captures an ordinary artefact– a dandelion clock – in a rare light and from the unique perspective of one man who happens to be living with dementia. While the dandelion clock is typically dismissed as a weed and has sometimes been used in a disparaging way to depict what’s happening to someone with dementia’s brain, this photograph demonstrates great vision and patience in capturing its extraordinary beauty. I’ve used this image repeatedly in my work over the years alongside the Henry David Thoreau adage ‘it’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see’.

These experiences eventually led me to complete a doctoral research study into the everyday citizenship of people living with dementia. James once again exerted an important influence through the pioneering work that he and fellow activists undertook with Professor Heather Wilkinson and others years before. Their efforts not only remedied the tendency to ignore, leave out or represent the perspectives of people with dementia in research, but also encouraged people with dementia to become co-researchers and teach researchers how to do research better. By the time I commenced my study, there was an expectation that men and women with dementia should expect to be actively and meaningfully involved in the creation of new knowledge and that principles of citizenship such as freedom from discrimination and having opportunities to participate and grow should be realised in research too. This made the research experience so much more rewarding for me and the people who took part and enriched the findings.

James’ influence continues. Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about the significance of the concept of ‘Opening Shutters, Opening Minds’ in light of the lockdown. The pandemic is exerting the greatest impact on people with dementia. While keen not to perpetuate the tendency to use body count as ‘the measure’ of the impact and course of the virus, it’s clear that a lot of people with dementia won’t come through the other side and this fact cannot be ignored. What’s more, many more people living with dementia (both those with a diagnosis and unpaid carers) will have deteriorated significantly as a result of the prolonged protection measures. Their anxiety and loss of confidence will be hard to redress. Yet there are many individuals and couples locking down who are exhibiting tremendous spirit and resilience. As we gradually begin to open the shutters in the months ahead, there will of course be a need to open minds – to the devastating consequences of the restrictions on the human rights of people living with dementia and to the important contributions that people living with dementia can and do make. It would be a fitting tribute to James and his fellow activists if this ‘opening of minds’ is led by people living with dementia. The publication of this book is a timely reminder of the type of support and encouragement needed to ensure their voices are heard – loud and clear.